via maedchenmannschaft.de

source: http://msmagazine.com

This is Part 1 of a four-part series on sexual objectification–what it is and how to respond to it.

The phrase “sexual objectification” has been around since the 1970s, but the phenomenon is more rampant than ever in popular culture–and we now know that it causes real harm.

What exactly is it, though? If objectification is the process of representing or treating a person like an object, then sexual objectification is the process of representing or treating a person like a sex object, one that serves another’s sexual pleasure.

How do we know sexual objectification when we see it? Building on the work of Nussbaum and Langton, I’ve devised the Sex Object Test (SOT) to measure the presence of sexual objectification in images. In it, I propose that sexual objectification is present if the answer to any of the following seven questions is “yes”:

1) Does the image show only part(s) of a sexualized person’s body?

Headless women, for example, make it easy to see them as only a body by erasing the individuality communicated through faces, eyes and eye contact:

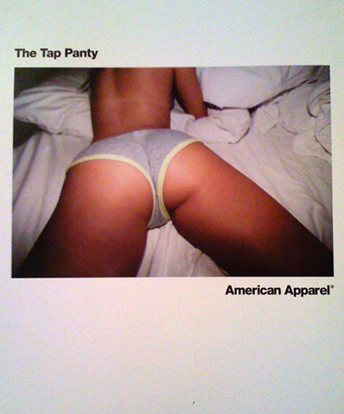

We achieve the same effect when showing women from behind, which adds another layer of sexual violability. American Apparel seems to be a culprit in this regard:

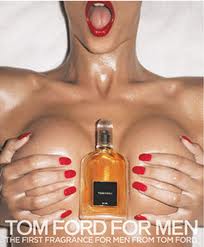

Covering up a woman’s face works well, too:

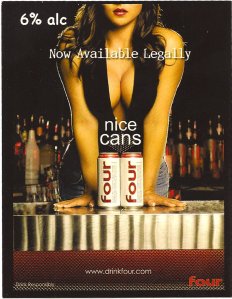

2) Does the image present a sexualized person as a stand-in for an object?

The breasts of the woman in this beer ad, for example, are conflated with the cans:

Likewise the woman in this fashion spread in Details, in which a woman becomes a table upon which things are perched. She is reduced to an inanimate object, a useful tool for the assumed heterosexual male viewer:

3) Does the image show sexualized persons as interchangeable?

Interchangeability is a common advertising theme that reinforces the idea that women, like objects, are fungible. And like objects, “more is better,” a market sentiment that erases the worth of individual women. The image below, advertising Mercedes-Benz, presents just part of a woman’s body (breasts) as interchangeable and additive:

This image of a set of Victoria’s Secret models, borrowed from a previous Sociological Images post, has a similar effect. Their hair and skin color varies slightly, but they are also presented as all of a kind:

4) Does the image affirm the idea of violating the bodily integrity of a sexualized person who can’t consent?

In this “spec” ad for Pepsi (not endorsed by the company), a boy is being given permission by the lifeguard to “save” an unconscious woman:

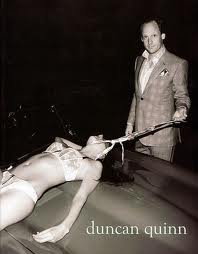

Likewise, this ad shows an incapacitated woman in a sexualized position with a male protagonist holding her on a leash. It glamorizes the possibility that he has attacked and subdued her:

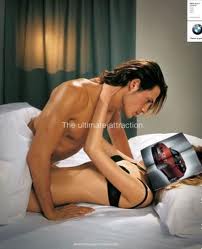

5) Does the image suggest that sexual availability is the defining characteristic of the person?

This American Apparel ad, with the copy “now open,” sends the message that this woman is open for sex. She presumably can be had by anyone.

6) Does the image show a sexualized person as a commodity that can be bought and sold?

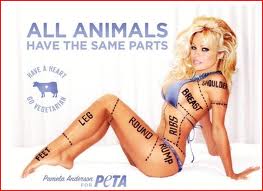

By definition, objects can be bought and sold, and some images portray women as everyday commodities. Conflating women with food is a common sub-category. This PETA ad, for example, shows Pamela Anderson’s sexualized body divided into pieces of meat:

In the ad below for Red Tape shoes, women are literally for sale and consumption, “served chilled”:

7) Does the image treat a sexualized person’s body as a canvas?

In the two images below, women’s bodies are presented as a particular type of object: a canvas that is marked up or drawn upon.

The damage caused by widespread female objectification in popular culture is not just theoretical. We now have more than 10 years of research demonstrating that living in an objectifying society is highly toxic for girls and women. I’ll describe that research in Part 2 of this series.

Cross-posted at Caroline Heldman’s Blog and Sociological Images